As the COVID-19 virus tightened its grip on the nation and the grim spring of 2020 gave way to an uneasy summer, I was one of the first staff members to return to in-person work at the Archives of American Art’s offices in downtown DC. Physically processing collections is one of the core duties of an archivist, and it can only be done onsite. So, after four months of telework, I ventured downtown to find boarded up buildings, shuttered businesses, and empty streets. It was a strange and disconcerting summer. Our building was largely vacant and although I was extremely grateful to have a job, navigating the few social interactions I had with masks and distancing only made me more aware of how much I had taken the freedom and ease of pre-pandemic life for granted. Amidst this unsettling new reality, I began work on processing the Dorothy Liebes papers and preparing them for digitization.

Having a window into the details of someone else’s life, at least as it reveals itself on paper, is a privilege of being an archivist that I try never to take for granted, and there are times when a collection assignment feels especially timely. Such was the case with the Dorothy Liebes papers. I could not have hoped for a better collection to work on during the dark days of the past year than that of this trailblazing weaver, textile designer, and colorist, whose vibrant world unfolded before me as late summer rolled into fall.

Far from having the time to pore over individual documents, most archivists need to work relatively quickly when processing a collection. Nevertheless, when working through collections that are particularly rich with primary sources produced by the creator, such as diaries, letters, writings, and photographs, an impression of the creator’s personality invariably surfaces. In this case, Liebes’s energy, talent, expertise, and charm did not so much emerge from her papers as leap from them. Her world was alive with color and innovation; her passion for her work was palpable in her correspondence with clients, friends, colleagues, and family. Her desk diaries alone made me dizzy with the number of appointments, lunch dates, dinner plans, and cocktail parties she would pack into her schedule day after day; and her draft autobiography was brimming with details and memories about people who helped and influenced her throughout her turbocharged career. Her scrapbooks were filled with press clippings, articles, and color magazine spreads that highlighted her accomplishments, documented the extent of her popularity and influence, and charted her ascent to household name in mid-century home design.

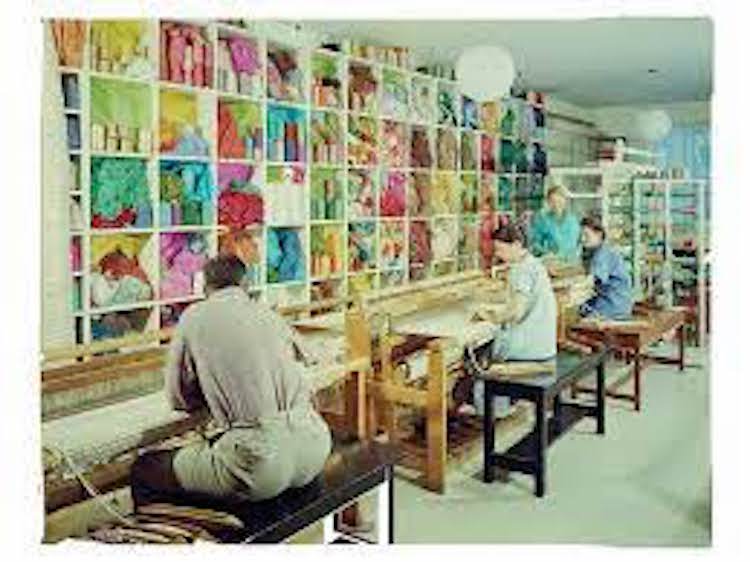

Liebes opened her first professional studio for weaving and textile design in San Francisco in 1934. She initially produced high-end custom work for architects, interior decorators, and designers. Her first major client in the textile industry was the Goodall Company in Sanford, Maine. Liebes was closely involved in working out the technical methods for producing her handmade designs on machine looms, enabling her to expand her client base in the man-made fiber industry, move into mass production of her designs, and ultimately make them available at lower price points.

Through her work with industry giants such as Dupont, Goodall, and Dobeckmun, Liebes was at the forefront of transforming the role of industrial fibers and influencing the home furnishings market with a new aesthetic in fabrics and textures. Her artistry as a weaver, her instinct for new trends and emerging tastes, and her business acumen combined to propel her to success.

But it is perhaps as a colorist that Liebes’s impact was most widely felt. If you’ve ever tossed a pillow on a piece of furniture to give your room a “pop” of color, you can thank Dorothy Liebes, whose decorative pillows were one of her signature innovations in home décor. “Yes. There’s nothing like what I call a ‘whameroo’ color to make the whole thing come alive,” she responded to designer Clare Potter when Potter remarked that she loved the way “you suddenly inject something startling.” By the early 1960s, Liebes had earned a reputation for being what one interviewer called “a pioneer in the use of clashing colors” or, as Liebes more poetically put it, colors that “vibrate together.” Liebes’s papers document her thinking on how to use and promote color, in detailed reports to clients about the industry markets she attended. In a 1960 letter to Arthur Gould of Dow Chemical’s Lurex Division, for example, Liebes foretells the ease with which she feels they will be able to promote Lurex—the metallic thread she had first tested for Dow (then Dobeckmun) in 1946—in the coming year, concluding: “Everywhere at the market color was on the march. There was no fear of using lots of it, and there were many interesting color combinations. The decorators’ floor (6th) was alive with color.”

Liebes always credited mother nature with being the original master of combining colors and spoke of the capacity of color to ease the mind. She was at the height of her career in turbulent times and was married, apparently happily, to Associated Press journalist Relman Morin from 1948 until her death in 1972.

Morin’s work repeatedly placed him in precarious, violent, and traumatic situations. He was imprisoned by the Japanese for six months during the Second World War and reported from the front lines of the European theater later in the war. Subsequent assignments found him reporting on the Korean War in 1951, witnessing the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in 1953, and documenting the trial of Holocaust perpetrator Adolf Eichmann in 1961. Morin also won a Pulitzer Prize (his second) for his eyewitness account of the vicious mob violence that erupted around him while he dictated his story from a phone booth, during the integration of Little Rock Central High School in 1957.

It is reasonable to assume, then, that when Liebes articulated her belief that “one reason for the popularity of vibrating colors is world tension…when we look at the headlines we need the gaiety and stimulation of color,” the world tension she spoke of came close to home on more than one occasion.

As the coronavirus ripped through the nation in 2020, for me it threw the need for a home to which one could safely retreat and find pleasure in into sharp relief, and Liebes’s papers invited me to reflect more deeply on how we build a home that can not only shelter us but can also sustain, comfort, and bring us joy in difficult times.

The “gaiety and stimulation of color” woven through this collection has certainly been a welcome balm for this archivist over the past year. Now that the papers of Dorothy Liebes have been digitized and are fully available online, the Archives invites you to take a closer look at the world that prompted Clare Potter to remark to Liebes in 1956 “Your studio is dazzling, Dorothy. Color, color everywhere.”

Stephanie Ashley is a processing archivist at the Archives of American Art.

Join us on Tuesday, September 14, 2021 from 12:30 p.m. to 1:15 p.m. for The Thread of the story: The Dorothy Liebes papers, part of the Cooper Hewitt’s Behind the Design series. This event is free but registration is required. For more information, visit: https://smithsonian.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_gsFYlf5hQ5Grd6J6vUL1jA